This time we consider spacetime $\mathbb{R}^{3+1}$ with the Minkowski metric $ds^2=-(dt)^2+(dx)^2+(dy)^2+(dz)^2$. (Here we set the speed of light in vacuum $c=1$). For each time slice i.e $t$=constant we get Euclidean 3-space and from what we know about Euclidean space there are rotations in the coordinate planes, the $xy$-plane, $yz$-plane, and $xz$-plane. What we have no clue about is rotations (from Euclidean perspective) in the $tx$-plane, $ty$-plane, and $tz$-plane. For that we consider $\mathbb{R}^{1+1}$ with metric $ds^2=-(dt)^2+(dx)^2$. Let $v,w$ be two tangent vectors to $\mathbb{R}^{1+1}$. Then $v,w$ are written as

\begin{align*}

v&=v_1\frac{\partial}{\partial t}+v_2\frac{\partial}{\partial x}\\

w&=w_1\frac{\partial}{\partial t}+w_2\frac{\partial}{\partial x}

\end{align*}

$ds^2$ acting on them results the inner product:

$$\langle v,w\rangle=ds^2(v,w)=-v_1w_1+v_2w_2=v^t\begin{pmatrix}

-1 & 0\\

0 & 1

\end{pmatrix}w$$

The last expression is obtained by considering $v$ and $w$ as column vectors (the reason we can do this is because every tangent plane to $\mathbb{R}^{1+1}$ is isomorphic to the vector space $\mathbb{R}^{1+1}$). Let $A$ be an isometry of $\mathbb{R}^{1+1}$. Let $v’=Av$ and $w’=Aw$. Then

\begin{align*}

\langle v’,w’\rangle&={v’}^t\begin{pmatrix}

-1 & 0\\

0 & 1

\end{pmatrix}w’\\

&=(Av)^t\begin{pmatrix}

-1 & 0\\

0 & 1

\end{pmatrix}(Aw)\\

&=v^tA^t\begin{pmatrix}

-1 & 0\\

0 & 1

\end{pmatrix}Aw

\end{align*}

In order for $A$ to be an isometry i.e. $\langle v’,w’\rangle=\langle v,w\rangle$ we require that $A^t\begin{pmatrix}

-1 & 0\\

0 & 1

\end{pmatrix}A=\begin{pmatrix}

-1 & 0\\

0 & 1

\end{pmatrix}$. A $2\times 2$ matrix $A$ satisfying

\begin{equation}

\label{eq:lo}

A^t\begin{pmatrix}

-1 & 0\\

0 & 1

\end{pmatrix}A=\begin{pmatrix}

-1 & 0\\

0 & 1

\end{pmatrix}

\end{equation}

is called an Lorentz orthogonal matrix. More generally a $4\times 4$ Lorentz orthogonal matrix $A$ satisfies

\begin{equation}

\label{eq:lo2}

A^t\begin{pmatrix}

-1 & 0 & 0 & 0\\

0 & 1 & 0 & 0\\

0 & 0 & 1 & 0\\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1

\end{pmatrix}A=\begin{pmatrix}

-1 & 0 & 0 & 0\\

0 & 1 & 0 & 0\\

0 & 0 & 1 & 0\\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1

\end{pmatrix}

\end{equation}

Let $A=\begin{pmatrix}

a & b\\

c & d

\end{pmatrix}$ be a Lorentz orthogonal matrix. We also assume that $\det A=1$ i.e. $A$ is a special Lorentz orthogonal group. Then we get the following set of equations

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

-a^2+c^2&=-1\\

-ab+cd&=0\\

-b^2+d^2&=1\\

ad-bc&=1

\end{aligned}

\label{eq:slo}

\end{equation}

Solving the equations in \eqref{eq:slo} simultaneously we obtain $A=\begin{pmatrix}

a & b\\

b & a

\end{pmatrix}$ with $a^2-b^2=1$. Hence one may choose $a=\cosh\phi$ and $b=-\sinh\phi$. Now we find a rotation matrix in the $tx$-plane

\begin{equation}

\label{eq:boost}

\begin{pmatrix}

\cosh\phi & -\sinh\phi\\

-\sinh\phi & \cosh\phi

\end{pmatrix}

\end{equation}

A friend of mine, a retired physicist named Larry has to confirm everything by actually calculating. For being a lazy mathematician I try to avoid messy calculations as much as possible, instead try to confirm things indirectly (and more elegantly). In honor of my dear friend let us play Larry. Let $\begin{pmatrix} t\\

x \end{pmatrix}$ be a vector in the $tx$-plane and $\begin{pmatrix} t’\\

x’ \end{pmatrix}$ denote its rotation by an angle $\phi$. (This $\phi$ is not really an angle and it could take any real value. It is called a hyperbolic angle.)

$$\begin{pmatrix} t’\\

x’ \end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix}

\cosh\phi & -\sinh\phi\\

-\sinh\phi & \cosh\phi

\end{pmatrix}\begin{pmatrix} t\\

x \end{pmatrix}$$

i.e.

\begin{align*}

t’&=\cosh\phi t-\sinh\phi x\\

x’&=-\sinh\phi t+\cosh\phi x

\end{align*}

and

\begin{align*}

dt’&=\cosh\phi dt-\sinh\phi dx\\

dx’&=-\sinh\phi dt+\cosh\phi dx

\end{align*}

Using this we can confirm that

$$(ds’)^2=-(dt’)^2+(dx’)^2=-(dt)^2+(dx)^2=ds^2$$

i.e. \eqref{eq:boost} is in fact an isometry which is called a Lorentz boost. In spacetime $\mathbb{R}^{3+1}$ there are three boosts, one of which is

$$\begin{pmatrix}

\cosh\phi & -\sinh\phi & 0 & 0\\

-\sinh\phi & \cosh \phi& 0 & 0\\

0 & 0 & 1 & 0\\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1

\end{pmatrix}$$

This is a rotation (boost) in the $tx$-plane. In addition, there are regular rotations one of which is

$$\begin{pmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 & 0\\

0 & \cos\theta & -\sin\theta & 0\\

0 & \sin\theta & \cos\theta & 0\\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1

\end{pmatrix}$$

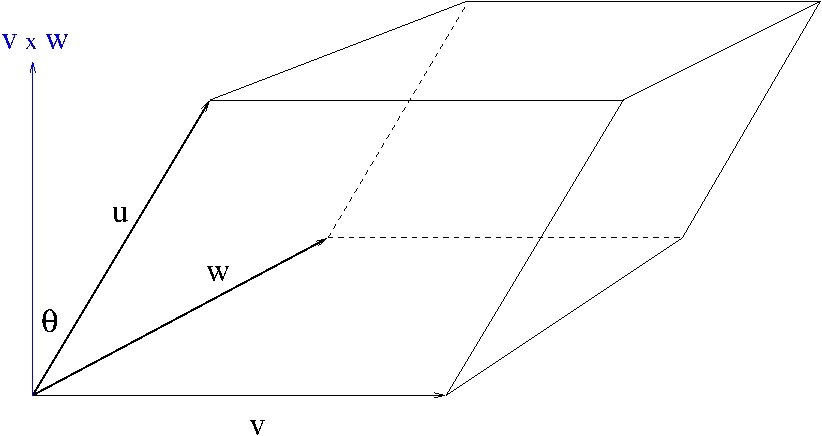

This is a rotation by the angle $\theta$ in the $xy$-plane. The three boosts and three rotations form generators of the Lorentz group $\mathrm{O}(3,1)$, the set of all $4\times 4$ Lorentz orthogonal matrices, which is a Lie group under matrix multiplication. As a topological space $\mathrm{O}(3,1)$ has four connected components depending on whether Lorentz transformations are time-direction preserving or orientation preserving. The component that contains the identity transformation consists of Lorentz transformations that preserve both the time-direction and orientation. It is denoted by $\mathrm{SO}^+(3,1)$ and called the restricted Lorentz group. There are 4 translations along the coordinate axes in $\mathbb{R}^{3+1}$. The three boosts, three rotations and four translations form generators of a Lie group called the Poincaré group. Like Euclidean motion group elements of the Poincaré group are affine transformations. Such an affine transformation would be given by $v\longmapsto Av+b$ where $A$ is a Lorentz transformation and $b$ is a fixed four-vector. The Lorentz group is not a (Lie) subgroup of the Poincaré group as the elements of the Poincaré group are not matrices. Note however that the Poincaré group acts on $\mathbb{R}^{3+1}$ in an obvious way and the Lorentz group fixes the origin under the group action, hence the Lorentz group is the stabilizer subgroup (also called the isotropy group) of the Poincaré group with respect to the origin.

I will finish this lecture with an interesting comment from geometry point of view. The spacetime $\mathbb{R}^{3+1}$ can be identified with the linear space $\mathscr{H}$ of all $2\times 2$ Hermitian matrices via the correspondence

\begin{align*}

v=(t,x,y,z)\longleftrightarrow\underline{v}&=\begin{pmatrix}

t+z & x+iy\\

x-iy & t-z

\end{pmatrix}\\

&=t\sigma_0+x\sigma_1+y\sigma_2+z\sigma_3

\end{align*}

where

$$\sigma_0=\begin{pmatrix}

1 & 0\\

0 & 1

\end{pmatrix},\ \sigma_1=\begin{pmatrix}

0 & 1\\

1 & 0

\end{pmatrix},\ \sigma_2=\begin{pmatrix}

0 & i\\

-i & 0

\end{pmatrix},\ \sigma_3=\begin{pmatrix}

1 & 0\\

0 & -1

\end{pmatrix}$$

are the Pauli spin matrices. The Lie group $\mathrm{SL}(2,\mathbb{C})$ acts on $\mathbb{R}^{3+1}$ isometrically via the group action:

$$\mu: \mathrm{SL}(2,\mathbb{C})\times\mathbb{R}^{3+1}\longrightarrow\mathbb{R}^{3+1};\ \mu(g,v)=gvg^\dagger$$

where $g^\dagger={\bar g}^t$. The action induces a double covering $\mathrm{SL}(2,\mathbb{C})\stackrel{2:1}{\stackrel{\longrightarrow}{\rho}}\mathrm{SO}^+(3,1)$. Since $\ker\rho=\{\pm I\}$, $\mathrm{PSL}(2,\mathbb{C})=\mathrm{SL}(2,\mathbb{C})/\{\pm I\}=\mathrm{SO}^+(3,1)$. $\mathrm{SL}(2,\mathbb{C})$ is simply-connected, so it is the universal covering of $\mathrm{SO}^+(3,1)$.

I will discuss some physical implications of Lorentz transformations next time.