When we studied second-order linear differential equations through undamped and damped harmonic motion, we made a hand waving argument that the general solution of a second-order linear differential equation is the linear combination of two distinct solutions that are linearly independent in the same sense as for vectors i.e. one solution is not a constant multiple of another solution. These solutions are called fundamental solutions. In this note, we discuss an important and intriguing relationship between second-order linear differential equations and linear algebra and explain why the general solution is given by the linear combination of two fundamental solutions. For the sake of simplicity, we limit our discussion to the case that characteristic equation has two distinct real solutions. In order to maintain this lecture note as much self-contained as possible, we include some of the basic concepts in linear algebra that we need for our discussion below.

Let us consider a second-order linear differential equation \begin{equation}\label{eq:2lde}\ddot{x}+p\dot{x}+rx=0\end{equation} \eqref{eq:2lde} can be written as a system of two first-order linear differential equations \begin{equation}\left\{\begin{aligned}\frac{dx}{dt}&=s\\\frac{ds}{dt}&=-ps-rx\end{aligned}\right.\label{eq:ldesys}\end{equation} Let $X=\begin{pmatrix}x\\s\end{pmatrix}$ and $A=\begin{pmatrix}0 & 1\\-r & -p\end{pmatrix}$. Then \eqref{eq:ldesys} can be written as the matrix differential equation $$\frac{dX}{dt}=AX$$

Definition. Let $A$ be a $2\times 2$ real matrix or equivalently a linear map $A: \mathbb{R}^2\longrightarrow\mathbb{R}^2$. A vector $v\in\mathbb{R}^2$ is called an eigenvector of $A$ if there exists a number $q\in \mathbb{R}$ such that $Av=qv$. The number $q$ is called an eigenvalue of $A$ belonging to the eigenvector $v$. We also say $v$ is an eigenvector associated with the eigenvalue $q$. Eigen is a German word and it means own or self. As you will see below, given an eigenvalue there are infinitely many eigenvectors that are associated with the eigenvalue but they are linearly dependent i.e one eigenvector is a scalar multiple of another. So the name makes sense.

How do we find eigenvalues of a matrix $A$? The equation $Av=qv$ is the same as $(A-qI)v=0$. In order for this equation to have a non-trivial solution ($v\ne 0$) it must be that \begin{equation}\label{eq:cheq}\det(A-qI)=0\end{equation} The equation \eqref{eq:cheq} is called the characteristic equation. You heard the name characteristic equation before when we discussed harmonic motion. While you must not see any resemblance, that characteristic equation and \eqref{eq:cheq} are the same thing, hence the name characteristic equation. For example, if $A=\begin{pmatrix}0 & 1\\-r & -p\end{pmatrix}$, $\det(A-qI)=q^2+pq+r$, so we see that $\eqref{eq:cheq}$ is the same as the characteristic equation $$q^2+pq+r=0$$ of the second-order linear differential equation \eqref{eq:2lde}. Again for the sake of simplicity, the rest of the discussion will be done using a simple example but the same idea applies to the general case. Let us now consider the second-order differential equation $$\frac{d^2}x{dt^2}+5\frac{dx}{dt}+6x=0$$ The matrix $A$ is $A=\begin{pmatrix}0 & 1\\-r & -p\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix}0 & 1\\-6 & -5\end{pmatrix}$ and $\det(A-qI)=q^2+5q+6=0$ has two distinct real solutions $q=-3, -2$. These are the eigenvalues of $A$. Now we find eigenvectors. For $q_1=-3$, $Av_1=q_1v_1$ with $v_1=\begin{pmatrix}a\\b\end{pmatrix}$ leads to the equation $b=-3a$. So we may choose $v_1=\begin{pmatrix}1\\-3\end{pmatrix}$. Similarly for $q_2=-2$, we find an eigenvector $v_2=\begin{pmatrix}1\\-2\end{pmatrix}$. These eigenvectors can be used to find solutions of $\frac{dX}{dt}=AX$. To see this let $Av=qv$ and $X(t)=f(t)v$. Suppose that $\frac{dX}{dt}=AX$. Then the function $f(t)$ is to be determined. \begin{align*}\frac{df(t)}{dt}v&=A(f(t)v)\\&=f(t)Av\\&=f(t)qv\end{align*} This implies that $$\frac{df(t)}{dt}=f(t)q$$ whose solution is $f(t)=Ae^{qt}$ where $A$ is a constant. So we see that $$X_1(t)=A_1e^{-3t}\begin{pmatrix}1\\-3\end{pmatrix}$$ and $$X_2(t)=A_2e^{-2t}\begin{pmatrix}1\\-2\end{pmatrix}$$ are solutions of $\frac{dX}{dt}=AX$. Since the equation is linear, their sum \begin{equation}\begin{aligned}X_1(t)+X_2(t)&=A_1e^{-3t}\begin{pmatrix}1\\-3\end{pmatrix}+A_2e^{-2t}\begin{pmatrix}1\\-2\end{pmatrix}\\&=\begin{pmatrix}A_1e^{-3t}+A_2e^{-2t}\\-3A_1e^{-3t}-2A_2e^{-2t}\end{pmatrix}\end{aligned}\label{eq:ldesyssol}\end{equation} is also a solution. It turns out that \eqref{eq:ldesyssol} is the most general solution of $\frac{dX}{dt}=AX$ meaning any solution would be in the form of \eqref{eq:ldesyssol}. To understand why this is the case let us first suppose that $A$ is a diagonal matrix $$A=\begin{pmatrix}q_1 & 0\\0 & q_2\end{pmatrix}$$ with $q_i\ne 0$, $i=1,2$. Let $X(t)=\begin{pmatrix}x_1(t)\\x_2(t)\end{pmatrix}$ be a solution of $\frac{dX}{dt}=AX$. Then $$\frac{dx_1(t)}{dt}=q_1x_1(t),\ \frac{dx_2(t)}{dt}=q_2x_2(t)$$ of which solutions are $$x_1(t)=A_1e^{q_1t},\ x_2(t)=A_2e^{q_2t}$$ Now $X(t)$ can be written as $$X(t)=\begin{pmatrix}A_1e^{q_1t}\\A_2e^{q_2t}\end{pmatrix}=A_1e^{q_1t}\begin{pmatrix}1\\0\end{pmatrix}+A_2e^{q_2t}\begin{pmatrix}0\\1\end{pmatrix}$$ Note that $\begin{pmatrix}1\\0\end{pmatrix}$ and $\begin{pmatrix}0\\1\end{pmatrix}$ are the eigenvectors of $A$ associated with the eigenvalues $q_1$ and $q_2$, respectively. Conversely, any matrix-valued function $X(t)$ of the form $X(t)=\begin{pmatrix}A_1e^{q_1t}\\A_2e^{q_2t}\end{pmatrix}$ satisfies the differential equation $\frac{dX}{dt}=AX$. Let $V$ be the set of all solutions of $\frac{dX}{dt}=AX$. Then $V$ is a vector space over $\mathbb{R}$. (The verification is straightforward and is left for readers.) The above argument shows that the linearly independent solutions $e^{q_1t}\begin{pmatrix}1\\0\end{pmatrix}$ and $e^{q_2t}\begin{pmatrix}0\\1\end{pmatrix}$ form a basis for $V$. So the dimension of $V$ is 2.

Remark. Let $V$ be the set of all infinitely differentiable functions. For $f,g\in V$ and $c\in\mathbb{R}$, define $f+g$ and $cf$ by \begin{align*}(f+g)(t)&=f(t)+g(t)\\(cf)(t)&=cf(t)\end{align*} Then $V$ forms a vector space over $\mathbb{R}$. So infinitely differentiale functions can be considered as vectors. The derivative $\frac{d}{dt}$ is a map $$\frac{d}{dt}: V\longrightarrow V;\ f\longmapsto \frac{df}{dt}$$ The well-known properties of the derivative: \begin{align*}\frac{d(f+g)}{dt}&=\frac{df}{dt}+\frac{dg}{dt}\\\frac{d(cf)}{dt}&=c\frac{df}{dt}\end{align*} ensure that $\frac{d}{dt}:V\longrightarrow V$ is indeed a linear map. Let $\lambda\in\mathbb{R}$. Then $f(t)=e^{\lambda t}$ is an eigenvector of $\frac{d}{dt}$ associated with the eigenvalue $\lambda$ because $\frac{de^{\lambda t}}{dt}=\lambda e^{\lambda t}$.

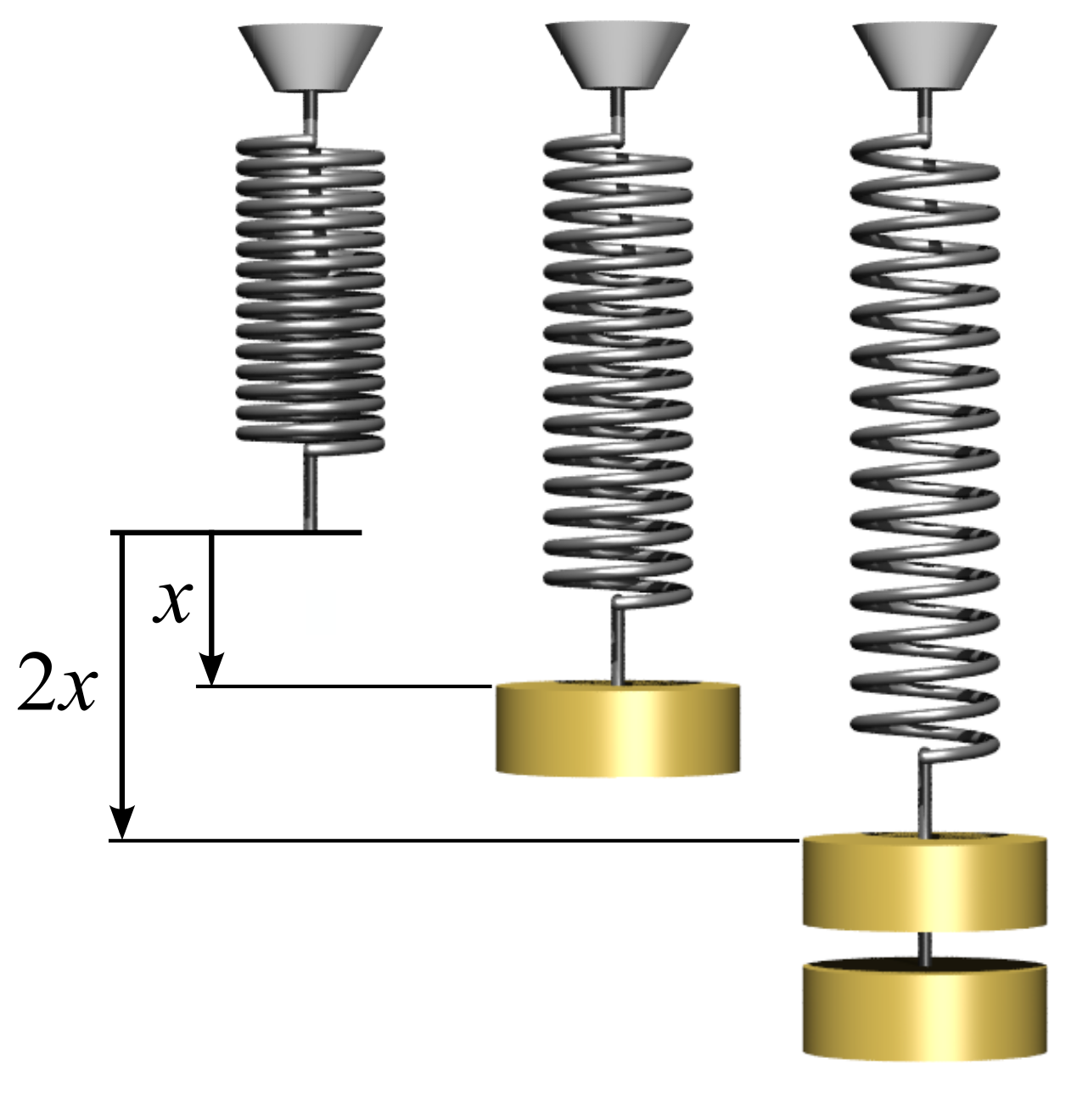

In our case, $A=\begin{pmatrix}0 & 1\\-r & -p\end{pmatrix}$ is not a diagonal matrix so the previous argument does not apply straightforwardly. However if $A$ has two distinct eigenvalues. then it is diagonalizable namely there is an invertible matrix $M$ such that $MAM^{-1}$ is a diagonal matrix. Such a matrix $M$ is called change of basis matrix. Note that $MAM^{-1}$ has exactly the same eigenvalues as those of $A$: \begin{align*}\det(MAM^{-1}-qI)&=\det(MAM^{-1}-M(qI)M^{-1})\\&=\det[M(A-qI)M^{-1}]\\&=\det(M)\det(A-qI)\det(M^{-1})\\&=\det(A-qI)\end{align*} If $v$ is the eigenvector of $A$ associated with the eigenvalue $q$, then $Mv$ is the eigenvector of $MAM^{-1}$ associated with the same eigenvalue $q$. To see this let $Av=qv$. Then \begin{align*}(MAM^{-1})(Mv)&=(MA)v\\&=M(Av)\\&=M(qv)\\&=q(Mv)\end{align*} Let $V$ be the ssolution space of $\frac{dX}{dt}=AX$ and $W$ the solutions apce of $\frac{dY}{dt}=(MAM^{-1})Y$. Since $M$ is invertible, $M: V\longrightarrow W$ is an isomorphism. For example, let $A=\begin{pmatrix}0 & 1\\-6 & -5\end{pmatrix}$ and $M$ change of basis matrix such that $MAM^{-1}=\begin{pmatrix}-3 & 0\\0 & -2\end{pmatrix}$. Set \begin{equation}\begin{aligned}M\begin{pmatrix}1\\-3\end{pmatrix}&=\begin{pmatrix}1\\0\end{pmatrix}\\M\begin{pmatrix}1\\-2\end{pmatrix}&=\begin{pmatrix}0\\1\end{pmatrix}\end{aligned}\label{eq:isobasis}\end{equation} Let $M=\begin{pmatrix}a & b\\c & d\end{pmatrix}$. Then \eqref{eq:isobasis} results in the systems of linear equations $$\left\{\begin{aligned}a-3b&=1\\a-2b&=0\end{aligned}\right.$$ and $$\left\{\begin{aligned}c-3d&=0\\c-2d&=1\end{aligned}\right.$$ whose solutions are $a=-2$, $b=-1$, $c=1$, and $d=3$. That is, $M=\begin{pmatrix}-2 & -1\\3 & 1\end{pmatrix}$ and we have $$MAM^{-1}=\begin{pmatrix}-2 & -1\\3 & 1\end{pmatrix}\begin{pmatrix}0 & 1\\-6 & -5\end{pmatrix}\begin{pmatrix}1 & 1\\-3 & 2\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix}-3 & 0\\0 & -2\end{pmatrix}$$ as expected. Recall from linear algebra that an isomorphism $M: V\longrightarrow W$ maps a basis of $V$ to a basis of $W$. So $e^{-3t}\begin{pmatrix}1\\-3\end{pmatrix}$ and $e^{-2t}\begin{pmatrix}1\\-2\end{pmatrix}$ form basis for $V$. Therefore $X(t)=A_1e^{-3t}\begin{pmatrix}1\\-3\end{pmatrix}+A_2e^{-2t}\begin{pmatrix}1\\-2\end{pmatrix}$ is the general solution of $\frac{dX}{dt}=\begin{pmatrix}0 & 1\\-6 & -5\end{pmatrix}X$ and consequently $x(t)=A_1e^{-3t}+A_2e^{-2t}$ is the general solution of the second-order linear differential equation $\ddot{x}+5\dot{x}+6=0$.